Engineering Is All About Girl Power

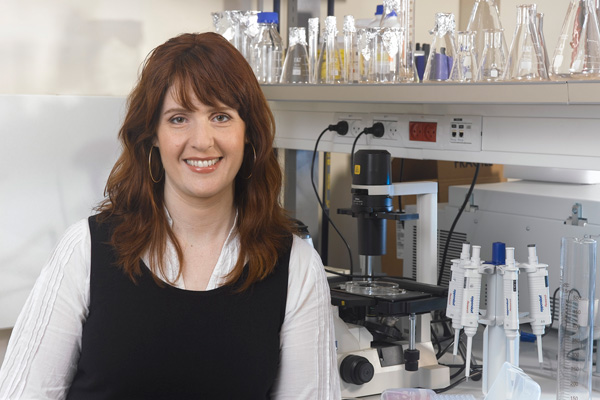

Prof. Rachela Popovtzer, Director of the Bioengineering study track at the Faculty of Engineering, knows exactly how to prompt women to choose a career in engineering – and she has no problem enrolling her students to helpProf. Rachela Popovtzer, Director of the Bioengineering study track at the Faculty of Engineering, knows exactly how to prompt women to opt for a career in engineering – and she has no problem enrolling her students to help

If you ask Prof. Rachela Popovtzer (45) whether engineering is a suitable field for women, you might get a surprised stare for an answer. “It’s the perfect field for women. It’s versatile, flexible, creative, and has an endless number of sub-specialties,” exclaims Popovtzer. “Moreover, it is applicable in almost any realm – security, medicine, military, technology – everything interfaces with engineering. It is also a very rewarding profession, offering many career trajectories and opportunities. There is absolutely no reason this field should be dominated by men. Women just have to go for it.”

Popovtzer certainly did. After completing her BSc in Physics and Philosophy at BIU, she pursued an MSc in Biomedical Engineering and a PhD in Electrical Engineering at Tel Aviv University. Her PhD focused on developing a biosensor containing genetically engineered bacteria, embedded into a biochip – an electronic device enabling functional detection of toxins. By the time she worked on her post doc at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, she was already a married mother of four. Two years later, she returned to Israel, landing directly at BIU’s Faculty of Engineering, where she is now heading the Bioengineering track.

“We develop technologies and imaging methods using nanoparticels. You could say that one of our main challenges it to develop methods for early detection of treatment efficacy. That is, analyzing whether the treatment route chosen (drugs or otherwise) is suitable and effective for the specific patient. It’s called patient stratification.”

In her Nano Theranostics lab she is currently supervising 10 female undergrads and one male student. “Even though the female students are more time-constrained, due to familial obligation, they are remarkable and amazingly capable. It’s all a question of motivation, ability and focus,” declares Popovtzer.

Today, only five out of 35 researchers are the faculty are women. Less than 20%. The number of female students in all degree tracks at the faculty is also significantly lower than that of the male students. Popovtzer says that it comes down to society’s gender tracking: “We know today that boys are gender tracked to analytical fields while girls are pushed towards the humanities as early as in grade school, despite the fact that many girls excel in math, physics and sciences. But our choice of profession is embedded at a much earlier age, according to role models we are exposed to. Female members of the family, TV and movie characters, and bedtime stories. I think science education should start at preschool. Instead of automatically suggesting that girls are princesses or teachers or dancers, we should introduce the notion of female engineers, doctors, or scientists. It’s pretty easy. We just have to present it in an appealing and age appropriate format, and break down what it actually means to be an engineer, or a pilot. Any profession can be presented in a fetching manner, and engineering is even easier because kids at that age are already familiar with computers and technology.”

To prompt girls to apply for a degree in engineering, the Faculty launched a program for the advancement of women in sciences five years ago. “The program exposes the possibilities and career opportunities of engineering to ninth-eleventh graders. We encourage them to focus on AP math and physics at school, and we also show them around the faculty’s facilities and labs, so that they can get a first-hand experience of what we do here. The point is to get them excited about our profession and illustrate that anyone can choose these professions, men or women.

“This program is very dear to my heart, and I make it a point to speak to these high school girls, visit the labs with them, and enroll all my female students to share the effort. Our faculty boasts its numerous female students who won scholarships from the Ministry of Science. One of the requirements of this scholarship program is hours of community service, and we enroll our female students to this program so they can visit the schools, talk to the girls (who are just a few years younger than they are), reach out to them and mentor them. The high schools girls are amazingly responsive, enthused and inspired by this program. I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard high school girls say – ‘I never thought about engineering as an option. I thought it was a boys’ profession.’

You really have to work hard to get people to stop and say – hey, why not?”

As for juggling a demanding profession with home life, Popovtzer is adamant: “One of the greatest advantages of this profession is its flexibility. You can pick your own pace. You can have kids and still stick to your planned track. You can choose when to focus on advancing and when to slow down, which is fine. You can slow down if you need to, cut down your hours, and still keep advancing your career and enjoy a meaningful, interesting and satisfying job. And you can always pick up the pace later on.

“I have supervised dozens of students in my years here, and even those who have babies at home, although putting in less hours than others, they still have incredible output, just as impressive as that of their fellow male students. I think women learn to be more focused and goal oriented. They come to work knowing they only have limited time to complete their tasks, and they make every effort to advance in their studies and work, so that their efforts are fruitful. As a matter of fact, students and researchers who are also young mothers, are equally successful as their male counterparts.”

Last Updated Date : 04/12/2022