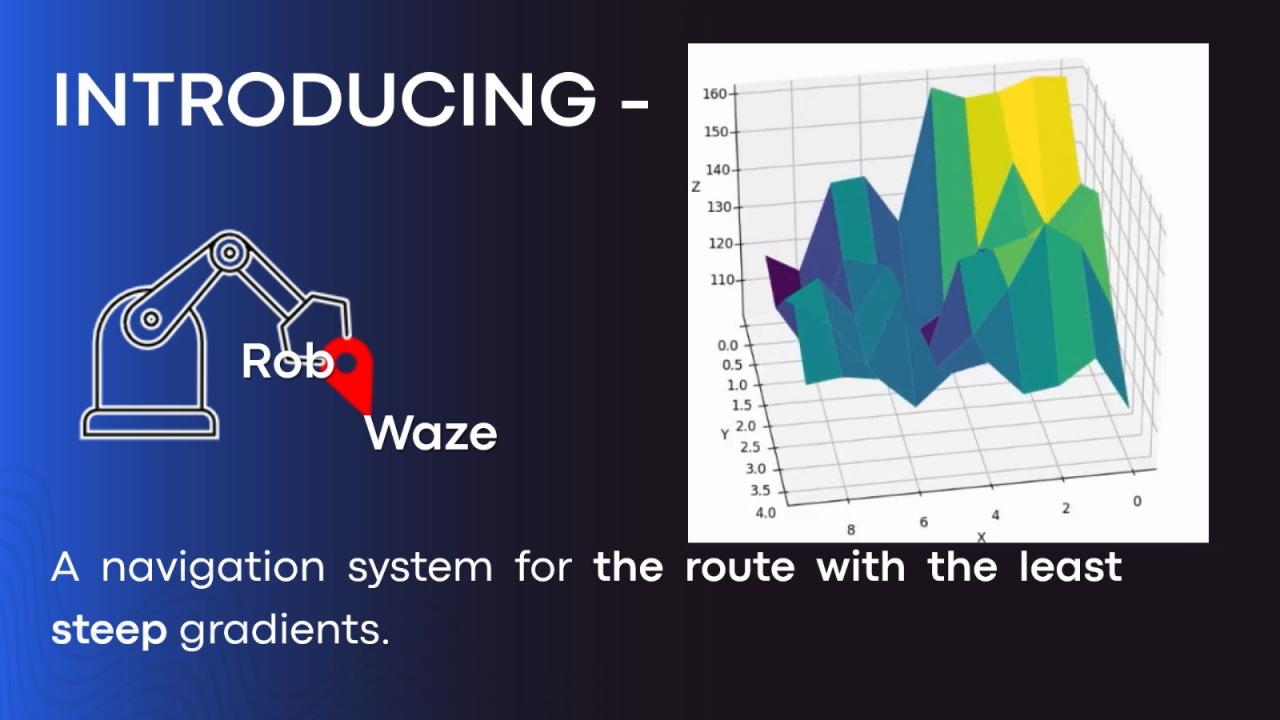

And the Third Place Goes to: Robo-Waze

Yair and David’s team developed a new, safe navigation system for robots. Using existing topographic maps, the system factors in elements like the robot’s weight and slope angles

The team that came third in the Hackathon is also the smallest team, comprising just two students: Yair Shmueli and David Goldzweig, both first-year Industrial Engineering and Information Systems undergraduates. “I learned of the hackathon concept from a friend who had recently won such a contest himself and thought it might be cool to partake in something similar. As soon as I heard of this year’s Hackathon, I realized I just had to sign up and go full throttle, given the significant potential to offer actual operational contributions. When I talked to David, I realized this was a guy with lots of motivation and spirit, and he agreed there and then,” says Yair Shmueli.

Yair and David set out to produce a safe navigation system for Yahalom Unit’s robots. “Yahalom Unit has a variety of robots used for different needs, like defusing explosives, reconnaissance or ground scanning. They enter places with limited access or life-threatening spots, as their operator sits back at a safe distance. If the robot gets in trouble or stuck, it could also fall down, fail or even end up in the wrong hands,” explains Yair. “One of the challenges posed to us at the opening session was finding the route with the most accessible slopes for the unit’s robot, given a topographic map of the area in question, because if the robot mounts a slope that’s too sharp, it could flip over, which has indeed happened before. Talking with the unit’s people, we learned it was a significant issue. We were surprised to learn that currently, the unit was only using civil navigation systems, like Google Maps, which don’t factor in slopes along the course. As a result, only a handful of highly experienced combat soldiers can navigate the robots across rough terrains. That’s why we wanted to design a system that would allow the safe, efficient operation of the robot, through all terrains, by any combat soldier.

The system developed by the pair was christened Robo-Waze. It comprised an interface to which a topographic map can be uploaded, with starting and finishing points, while the system offers every robot the safest route, taking on board its total weight, so as to rule out unsuitable routes. “At the end of the day, the combat soldier who operates the robot gets a 3D map, charting all the slopes. The safest route for the robot is highlighted on the map, allowing the soldier to chart the course in the most suitable manner,” explains Yair. “At the moment, the system can only measure the topographic terrain, which will inform us of slopes on the ground, but in the future, we may be able to introduce additional functions, to handle other obstacles, like bushes or buildings along the way. This is a major step forward towards a future where we could dispatch autonomous robots because once a safe route has been charted, the robot can set out on its own, which will also allow us to keep our forces safe.”

Work on the system mainly involved programming and code writing. “With no more than a semester-worth of Python programming know-how, I ended up as the programmer of the team. But we realized that with a little help, we could make the system run, so without thinking twice, we would consult the mentors, asking for their opinion. We received plenty of good advice, of which only some we had the chance to implement,” says Yair, citing the help they enjoyed along the way from mentors, notably N., a former combat soldier with the unit and an engineering student himself. “At the early stages, we delivered a 3-minute pitch for the judges. David created the presentation, while I practiced the pitch for an hour, fine-tuning it. We also put a lot of thought into the marketing side of things: not just the presentation, but also the name, logo, and branding. I believe it eventually paid off.”

The pair’s system earned them the third spot in the contest, with a prize of 3,000 NIS, “but we both agree that the important bit is the experience gained in the run-up to and during the contest,” declares Shmueli. “The fact that we managed to take different theoretical tools gained from lectures we’d attended in our various courses, and turn them, at 3:50 PM, into a running code, based on nothing but a first-year knowledge – for us, that’s the real victory. Plus, we value the fact that we’ve developed something of significance that could even help save lives, and much to our delight, we’ve been in touch with the unit, with the purpose of taking this idea to the operational level.”

.jpeg)

Last Updated Date : 28/06/2023